Street Art & Social Justice

Street art embodies a unique intersection of aesthetic, public space, and social criticism. The accessibility of the art form contributes to the power of its message, as it confronts people in their everyday environments with injustices that are otherwise easily ignored. Coffey (2012) contends that murals have historically been used to convert energies of revolution “into an ethical impulse to socialize artistic expression and to place art in the service of building a new, more equitable society” (p. 1). Street artists inspire hope and change by transforming public space, using art as activism.

Street Art in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside

Street art can be found all around the Downtown Eastside, from building fronts to back alleys. Each mural has a unique message related to the community and its history, pointing to the social injustices that shape the lives of individuals who live and work there. Their calls for social justice speak loud and clear to passersby, community workers, police, and so on. Many of these justice-oriented murals shine light on the structural violence that continues to marginalize individuals in the Downtown Eastside.

Take a Virtual Walk Through the Downtown Eastside

Social analysis is critical for social workers to understand how structures of power reproduce oppression and disadvantage for individuals. By engaging in relational reflexivity and deconstructing their own knowledge and power, social workers have the opportunity to challenge societal norms that perpetuate inequality (D’Cruz, Gillingham, & Melendez, 2007, p. 79).

The Downtown Eastside is a highly stigmatized community wherein its residents are often pathologized amidst addiction, poverty and homelessness. Williams (2011) reminds us that “by endorsing the status quo, norms perpetuate inequalities, without even drawing attention to domination” (p. 170). Acknowledging our own complicity in perpetuating hierarchies of inequality is an important step to overturning these norms and empowering marginalized communities. By deconstructing the context-specific nature of interlocking oppressions and axes of disadvantage related to class, race, gender, and disability experienced by the residents of the Downtown Eastside (Hulko, 2009), I wish to reconstruct the strong sense of hope that each mural represents in order to move toward a more socially just and caring society.

Take a virtual walk among the street art of the Downtown Eastside and learn about its history, its residents, and their calls for justice.

1. Healing Quilt (2017) by Jerry Whitehead, Sharifah Marsden and Corey Larocque. Hastings Urban Farm, Abbott St. & Carrall St.

(Photo by Gilpin, E., 2017. Retrieved from https://thetyee.ca/Culture/2017/09/11/Downtown-Eastside-Community-Spirit/)

(Photo by Gilpin, E., 2017. Retrieved from https://thetyee.ca/Culture/2017/09/11/Downtown-Eastside-Community-Spirit/)

The Healing Quilt, featuring a thunderbird and a star blanket, reads “There’s no one to care if you do not care, Bud Osborn 1947-2014” honoring a Downtown Eastside resident and revered poet. The piece honors the victims of Vancouver’s opioid crisis (Gilpin, 2017).

Residents of the Downtown Eastside who are active in addiction are regularly criminalized, surveilled, and marginalized because of their hyper-visibility in the place-based margins of poverty. This memorial mural acts as a stark reminder for social workers that poverty, homelessness, and addiction are not individual problems but constitute structural violence that has dire consequences for marginalized communities.

2. Through the Eye of the Raven (2010) by Haisla Collins, Sharifah Marsden, Richard Shorty, Eric Parnell, and Nicola Campbell. Orwell Hotel, 456 E Hastings St.

(Photo by Johnston, L. B., 2017. Retrieved from http://www.yukon-news.com/news/brightening-up-vancouvers-east-side-through-the-ravens-eye/)

“The Raven Dancer, dressed in a traditional button robe, holds the ‘Looking Forward, Looking Back’ symbol, signifying the importance of the past when viewing the present, and looking to the future. In ‘Through the Eye of the Raven,’ the light of day is cast upon what, for many on Vancouver’s Eastside, is a dark and forbidding place. Yet the Raven sees past the troubles of this time, alighting upon the sacred canoe of the Coast Salish and reminding us of the rich and powerful heritage that is the birthright of Aboriginal people. Salish serpents and patterned braids frame the mural, while animals walk along the hem of Raven’s blanket. This button blanket enfolds both the terror of the residential school system, as well as the strength and courage of those who stand up and speak for justice. Finally, the hummingbird, a Tutchone symbol of hope, flies above the Vancouver cityscape towards the light.” (Creative Cultural Collaborations Society, 2017, Through the Eye of the Raven)

This mural conveys defiance and empowerment, representing both the rich culture of the Coast Salish people and the history of colonialism that continues to perpetuate racism and violence against First Nations people in this community.

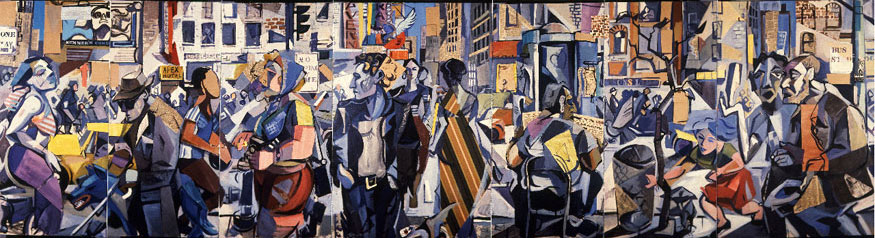

3. Historical Mural 1855-1955 (2017) by Ilya Viryachev. PiDGiN, 350 Carrall St.

(Retrieved from http://scoutmagazine.ca/2017/06/29/goods-special-july-18-dinner-at-pidgin-set-to-celebrate-long-awaited-alley-mural-debut/)

“The mural at 350 Carrall by Ilya Viryachev is meant to symbolize the history of Vancouver, concentrating primarily on its surroundings between 1855-1955. It is impossible to include every significant event over a century on one wall, so rather we aimed to represent various significant processes to reveal how Vancouver’s current model of tolerance and multiculturalism was forged through histories of violence, racism and inequality.” (PiDGiN, 2017)

The mural depicts the historical colonization, racism, violence and displacement that is embedded in Vancouver’s history. Ironically, the trendy restaurant which hosts this beautiful piece is a perfect example of the gentrification process that is currently displacing residents and businesses in the Downtown Eastside.

4. Radius (2017) by Eri Ishii, Gerald Pedros, Richard Tetrault, Jerry Whitehead and June Yun, Marissa Nahanee, Christine Chung and Mayuka Hisata. 280 E Cordova St.

(Photo by McGrath, T., 2014. Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/time-to-look/13146761605)

“The Radius mural represents three distinct communities that converge in the Downtown Eastside: Aboriginal, Chinese and Japanese. The mural was conceived to reflect themes of origin and place, weaving together material gathered from outreach workshops into the design. The team of artists and mentored youth come from each of these communities.” (Creative Cultural Collaborations Society, 2017, Radius)

This mural represents the cultural diversity of this community and strong sense of hope and empowerment in community collaboration. For social workers, it conveys the strength that comes from engaging in reflexive praxis and learning from communities rather than showing up with preconceived assumptions about who they are.

5. Snapshots of History (2010) by Shu Ren Cheng. 490 Columbia St.

(Photo by Creative Cultural Collaborations Society, 2017. Retrieved from http://vancouvermurals.ca/tour-a/490-columbia/)

(Photo by Creative Cultural Collaborations Society, 2017. Retrieved from http://vancouvermurals.ca/tour-a/490-columbia/)

“Snapshots of History is a visual time machine. One panel depicts the Goon family. Hung Get Goon, dreamt of becoming a lawyer, but was never able to go to law school due to discrimination. Instead, his father became the city editor of the Chinese Times while his mother, Ruth, ran a fish shop in Chinatown. The other two panels of the mural feature a reproduction of a 1905 photo of a silk merchant in Chinatown and a rendering of a 1936 photo of men sitting outside a barber shop at Carrall and Pender. The mural is significant because it embodies the indefatigable spirit of the Chinese to persevere no matter where they are in the world, hoping the hard work sewn by one generation will be reaped by the next. At the inauguration Goon’s son commented ‘I think it’s an excellent, excellent idea. It’s in memory of our ancestors and how they came out here and how hard it was for them to begin life here in Canada. There was so much discrimination. It was really hard for them to get by — but they survived, they survived.’” (Creative Cultural Collaboration Society, 2017, Snapshots of History)

This mural sits on the border of the Downtown Eastside and Chinatown and reminds social workers of the realities of discrimination and exclusion that are produced through the axes of intersecting social locations of socioeconomic class and race.

6. Living Wall (2010) by Steve Hornung. 319 Main St. (Alleyway).

(Photo by Creative Cultural Collaborations Society, 2017. http://vancouvermurals.ca/tour-a/319-main-street-2/)

“The mural was part of a ‘Grey to Green,’ initiative to improve livability in the alley for local residents and workers. The mural was part of the RestART inititive created by restoriatice justice practitioners in collaboration with VPD Anti-Graffiti Unit; it involved 9 youths and 7 members of community as a team building and skills development component to help beautify and increase the perception of safety in the laneway.” (Creative Cultural Collaborations Society, 2017, Living Wall)

The Living Wall fosters hope by making visible the spaces that are occupied by marginalized individuals in this community.

7. We Take Care of Each Other (2009) by Anne Marie Slater, Scott Chan, and Coleman Webb. 601 Keefer St.

(Photo by Creative Cultural Collaborations Society, 2017. Retrieved from http://vancouvermurals.ca/tour-b/601-keefer-street/)

This piece is an artist-led collaboration with the community; the image was derived from a think tank of 200 children led by Kid’s at Heart Collective. “The mural is a story of children’s voices that speak of this special place; their community” (Creative Cultural Collaborations Society, 2017, We Take Care of Each Other).

This mural represents a unique collaboration across ages, engaging youth in the creation of sustainable “intergenerational urban space” that is grounded in collaborative action and harmony (Biggs & Carr, 2015, p. 109).

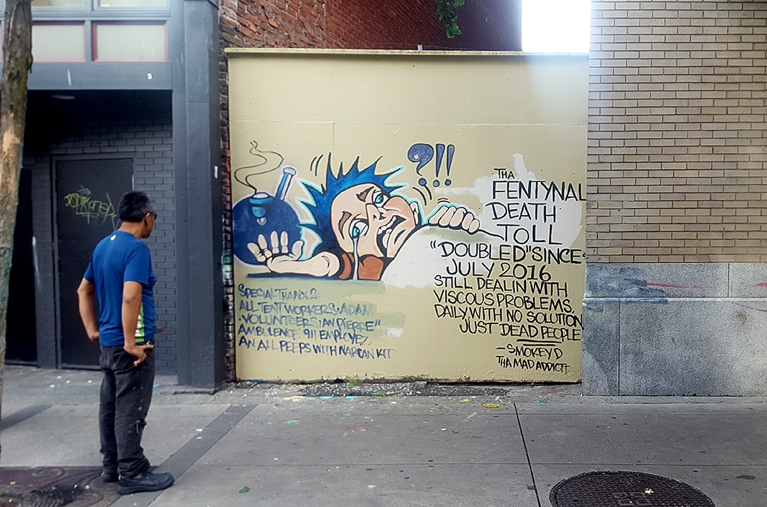

8. Untitled (2017) by Smokey D., 433 Carrall St.

(Photo by Lawrence, 2017. Retrieved at http://www.westender.com/news-issues/vancouver-shakedown/dtes-graffiti-artist-smokey-d-earns-permission-to-paint-opioid-crisis-memorial-1.22230894)

This mural is one of many created by street artist Smokey D. in the Downtown Eastside. His pieces, often removed by business owners and recreated by the artist, are known for “graphically chronicling the latest opioid death count or leaving tributes to fallen friends. The paintings . . . serve as a harsh reminder of the very real health crisis gripping one of the most vulnerable neighbourhoods in Canada” (Lawrence, 2017)

Social problems are often seen as individual problems, perpetuating structural violence that harms marginalized individuals until these structures are made visible (Taylor, 2013, p. 259). As social workers, we must challenge norms that perpetuate hierarchical inequalities, justify lacking resources, and disregard drug users in the Downtown Eastside. This indifference constitutes structural violence, or “violence that occurs in the context of establishing, maintaining, extending, or reducing hierarchical relations between categories of people within a society” (Iadicola & Shupe, 2003, p. 316, as cited in Taylor, 2013, p. 257).

9. Naa Tsmah (2017) by Larissa Healy and Shadae Johnson. Army & Navy Dept. Store, 36 W Cordova St. (South Alleyway).

(Photo by Ohrn, K., 2017. Retrieved from https://pricetags.wordpress.com/2017/09/05/public-art-army-navy-building/)

“Naa Tsmah – meaning ‘one heart one mind’ this mural is representative of the living in two worlds. The artist team will paint their stories of what it means to be people of the unceded Coast Salish lands while sharing the land with immigrants who have made this their home.” (Ohrn, 2017)

Organized by Spacing Vancouver, a public art initiative of Canada 150+, this mural conveys the resilience and resistance of Indigenous people in the face of ongoing colonization of their land.

10. Soul Gardens (2011) by Jordan Bent, Indigo, Scott Sueme, Melanie Shambach, and Take5. Astoria Hotel, 769 E Hastings St.

(Photo by AHA Media, 2011. Retrieved from https://ahamedia.ca/2011/11/18/w2-soul-gardens-mural-cultural-history-of-the-vancouver-downtown-eastside-dtes/)

“Soul Gardens is a community public art project led by W2 Community Media Arts that investigates the cultural history of the Downtown Eastside (DTES) as told through stories of food, gardening, and community.” (Creative Cultural Collaborations Society, 2017, Soul Gardens)

“From lead artist researcher Cease Wyss: ‘The Skwxwu7mesh quote used in this work “ha7lh en skwalwen” which translates as “my heart feels good” is a reminder that the First Languages, like the First Peoples, continue to thrive and live here. The Salmon represent resilience, as well as hope for sustainability. The Woman and the Child represent what we are holding onto, and what we are reaching for: hope and life. The visual stories represented in this mural weave themselves into the many culturally diverse groups of neighbors and what we all share in our daily lives, and a hope for those who view it daily to be lifted up during their work at the garden or their daily commute, or even just their walk in the hood.'” (City of Vancouver, 2017, Soul Gardens Mural Project)

This mural represents hope and strength in learning from diverse communities. It challenges dominant discourses that erase and exclude Indigenous people from the Canadian narrative.

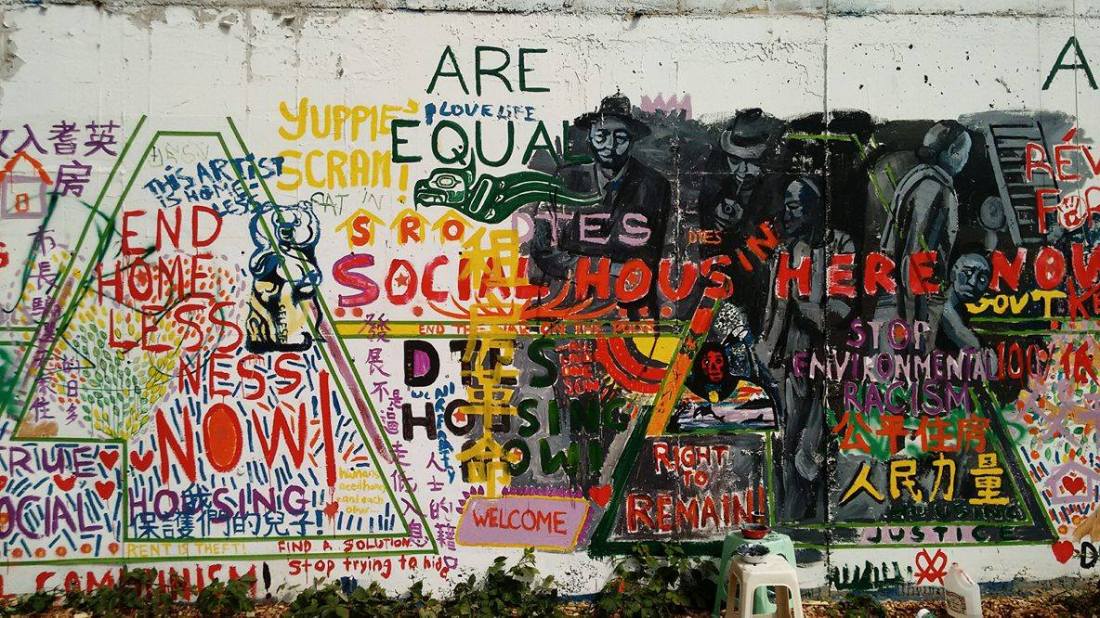

11. Untitled (2016) by Downtown Eastside community members. 58 W Hastings (removed).

(Photo by Boothroyd, G., 2016. Retrieved from http://themainlander.com/2016/05/31/only-fraction-of-new-social-housing-units-in-vancouver-guaranteed-for-low-income-people/)

This mural was painted by residents of the Downtown Eastside, protesting the city’s 2016 plan for a housing development at 58 W Hastings which would include only a small fraction of social housing units (Boothroyd, 2016). Months later, following extensive protest by the community and pressure from the Tent City occupying the vacant lot, Mayor Gregor Robertson committed to 100% social housing in the new development.

This mural represents the community’s call to action for ending homelessness. Taylor (2013) reminds us that “homelessness is place-based marginalization . . . the visible reminder of what are otherwise hidden hierarchical social mechanisms of oppression” (p. 263). Homelessness is a social problem not an individual one and social workers must challenge the structural violence that strives to annihilate and exclude homeless people from occupying unconventional public space.

Critical Hope & Creative Activism

These living art forms transform public space but they also remind social workers that our practices of social care must be connected to social justice. The presence of these powerful murals are a daily reminder of the social injustices that disempower the residents of the Downtown Eastside. However, they also represent what Campbell and Baikie (2012) call “critical hope,” a hopeful action that recognizes the structures that produce injustice and envisions a just world (p. 67).

As seen in these pieces, community members and artists have utilized street art for “creative activism” wherein public space and the community itself become a site for hope, collective action, and meaningful social change (Forde & Lynch, 2014, p. 2086). By deconstructing knowledge, power, and privilege, social workers can engage in empowering relationships and collective action alongside marginalized communities.

I hope this virtual tour of street art in the Downtown Eastside has inspired you to walk alongside the resilient artists and individuals who reside in the community and amplify their bold calls for justice.

References

Biggs, S., & Carr, A. (2015). Age- and Child-Friendly cities and the promise of intergenerational space. Journal of Social Work Practice, 29(1), 99 – 112.

Boothroyd, G. (2016, May 31). Only fraction of new social housing units in Vancouver guaranteed for low-income people. Retrieved from http://themainlander.com/2016/05/31/only-fraction-of-new-social-housing-units-in-vancouver-guaranteed-for-low-income-people/

Campbell, C., & Baikie, G. (2012). Beginning at the beginning: an introduction to critical social work. Critical Social Work, 13(1), 67-81.

City of Vancouver. (2017). Soul Gardens Mural Project. Retrieved from http://covapp.vancouver.ca/PublicArtRegistry/ArtworkDetail.aspx?FromArtworkSearch=False&ArtworkId=514

Coffey, M. K. (2012). Introduction. In How a revolutionary art became official culture: murals, museums, and the Mexican state. Durham: Duke University Press.

Creative Cultural Collaborations Society. (2017). Living Wall. Retrieved from http://vancouvermurals.ca/tour-a/319-main-street-2/

Creative Cultural Collaborations Society. (2017). Radius. Retrieved from http://vancouvermurals.ca/tour-b/radius/

Creative Cultural Collaborations Society. (2017). Snapshot of History. Retrieved from http://vancouvermurals.ca/tour-a/490-columbia/

Creative Cultural Collaborations Society. (2017). Through the Eyes of the Raven. Retrieved from http://vancouvermurals.ca/tour-b/456-hastings/

Creative Cultural Collaborations Society. (2017). We Take Care of Each Other. Retrieved from http://vancouvermurals.ca/tour-b/601-keefer-street/

Creative Cultural Collaborations Society. (2017). Soul Garden. Retrieved from http://vancouvermurals.ca/tour-c/soul-garden/

Block, D. & Corona, V. (2014). Exploring class-based intersectionality. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 27(1), 27-42.

Forde, C., & Lynch, D. (2014). Critical practice for challenging times: Social workers’ engagement with community work. British Journal of Social Work, 44(8), 2078 – 2094.

Gilpin, E. (2017, September 11). Something Bright for a Community of Spirit. Retrieved from https://thetyee.ca/Culture/2017/09/11/Downtown-Eastside-Community-Spirit/

Hulko, W. (2009). The time and context contingent nature of intersectionality and interlocking oppressions. Affilia, 24(1), 44 – 55.

Lawrence, G. (2017, August 28). DTES graffiti artist Smokey D. earns permission to paint opioid crisis memorial. Retrieved from http://www.westender.com/news-issues/vancouver-shakedown/dtes-graffiti-artist-smokey-d-earns-permission-to-paint-opioid-crisis-memorial-1.22230894

Ohrn, K. (2017, September 5). Public Art – Army & Navy Building. https://pricetags.wordpress.com/2017/09/05/public-art-army-navy-building/

PiDGin. (2017). Historical Mural 1855-1955. Retrieved from http://www.pidginvancouver.com

Taylor, S. (2013). Structural Violence, oppression, and the place-based marginality of homelessness. Canadian Social Work Review, 30(2): 256 – 73.

Weinberg, M. (2008). Structural social work: a moral compass for ethics in social work. Critical Social Work, 9(1).

Williams, Dana. 2011. “Why revolution ain’t easy”: violating norms, re-socializing society. Contemporary Justice Review, 14(2), 167 – 87.